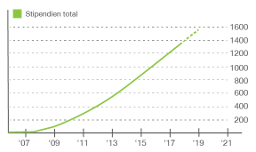

Our clear focus on sustainable impact and newly launched goal to empower 1'000 Young Entrepreneurs have allowed us to take the lead.

Blog

Explainer: why Kenya wants to overhaul its entire education system

Posted on 08/28/2016 at 01:43PM

This test was written by Daniel Sifuna, Professor of History of Education, Kenyatta University. It was first published on Mon, 15/08/2016 on THE CONVERSATION.

Kenya is reforming its education system for the first time in 32 years. It’s also changing its curriculum from pre-school all the way through to high school.

Part of what’s prompted this huge overhaul is the realisation that Kenya isn’t doing enough to produce school-leavers who are ready for the world of work. The government’s own assessments have showed that the current system isn’t flexible. It struggles to respond to individual pupils’ strengths and weaknesses.

In this article I’ll explain what the current Kenyan education system looks like. I’ll explore its weaknesses and then unpack how the new structure that’s being proposed hopes to tackle these.

The status quo

Kenya operates on an 8-4-4 education system. This was introduced in 1985 and based on a presidential commission’s recommendations. Under this system, pupils had to complete eight years of primary schooling and four at the secondary level. University degrees took a minimum of four years to complete. The whole system’s guiding philosophy was education for self-reliance.

There have been some reviews and evaluations since then. These have mostly addressed curriculum content issues and tidied up areas where there’s unnecessary overlap. The reviews haven’t adequately addressed fundamental issues. If these issues are tackled, the education system could transform Kenyan society by enhancing all citizens’ productivity and accelerating economic development.

Then in 2008 the Kenyan Institute of Education produced an evaluation report about the 8-4-4 system. It found that the system was very academic and examination oriented. The curriculum was overloaded. Most schools, the institute reported, weren’t able to equip their pupils with practical skills. Many teachers also weren’t sufficiently trained.

The evaluation report pointed out that secondary school graduates didn’t have very many entrepreneurial skills – the sort needed for self-reliance. High unemployment arises from this phenomenon. There’s also the risk of social vices emerging among those youngsters who aren’t prepared for the world of work. The institute worried about increased levels of crime, drug abuse and antisocial behaviour.

It also found that the existing system wasn’t providing flexible education pathways. These are important for identifying and nurturing learners’ aptitudes, talents and interests early enough to prepare them for the world of work and career progression. This lack of flexibility was found to be pushing up drop-out rates, even among academically talented pupils.

One of the biggest problems was a focus on exam results. The system didn’t seem to care whether pupils had the skills and knowledge they needed at different levels. It just wanted them to perform well on written assessments.

A new approach

The Kenyan government decided to take action. Drawing from the institute’s evaluation and a 2012 report by the Ministry of Education, it developed a plan to reform education and training. This stated that the sector should be guided by a national philosophy that places education at the centre of Kenya’s human and economic development.

Some of the plan’s aims include:

- developing learners’ individual potential in a holistic, integrated manner while producing intellectually, emotionally and physically balanced citizens;

- introducing a competency-based curriculum that focuses on teaching and learning concrete skills rather than taking an abstract approach;

- establishing a national assessment system that caters for the continuous evaluation of learners;

- putting in place structures to identify and nurture children’s talents from an early age; and,

- introducing national values, cohesion and integration into the curriculum. This will, it’s hoped, promote a Kenyan society whose values are harmonious and non-discriminatory.

Another important element of the plan is an emphasis on science, technology and innovation. The current education system doesn’t provide a strong foundation for developing such skills. The proposed new system will try to develop vocational and technical skills in a bid to meet Kenya’s demand for skilled labour and its push for greater industrialisation.

Three tiers

The new system that’s being proposed will involve a three-tier approach to education.

Tier one is described as the early years of education. It focuses on what the plan calls the “foundational skills of literacy and numeracy”. It will consist of pre-primary and lower primary school. Kindergarten and primary school grades one to four will offer general education. Grades five and six will centre on academic subjects, including languages, sciences and arts.

Tier two will concentrate on “curriculum exploration, abilities and interests, as well as pathways for high school”. It will cover grades seven to 12 and offer subjects that are relevant to some generalised learning areas. This will allow learners to firm up their interests and strengths.

Finally there’s tier three. This will combine senior school education and tertiary training. It will offer more specialised and targeted competencies that prepare learners either for vocational, college or university education.

By the end of this level, learners should be equipped with the skills they’ll need to either be self-reliant – entrepreneurs – to join the labour market, pursue a diploma or enrol for a university degree. College education, technical and vocational training would last for two years. An average university degree would be three years long.

University education also has its critics. They argue that Kenyan universities are not preparing students well for the job market. Reform, if it happens, will be led by the Commission for University Education and individual universities.

The process

So, the plan exists. Now it must be brought to life. Policies must be formulated. Curricula must be designed. Every subject’s syllabus needs to be developed and approved. Curriculum support materials – course books and teachers’ guides, handbooks and manuals – must be developed.

Teachers, education officers and other stakeholders must be trained and prepared for all of these changes. Then it will be time to select pilot schools where the new plan can be put to the test. Once this is done, it’s on to national implementation and a crucial period of monitoring and evaluation.

This is an ambitious, important process. Can it be done? Yes – but only if the national government of Kenya puts its money where its mouth is and invests comprehensively. Overhauling the curriculum will require a great deal of physical and human resources; a proper financial investment is critical.

Jetzt spenden

Jetzt spenden